Chef Mike Kalanty visits Wood Stone

Chef and artisan baker Mike Kalanty stopped by our test kitchen last week to pick Wood Stone Chef Tim Green’s brain about breads out of our ovens. He generously agreed to let us capture some images and even provided us with his thoughts on the experience. You can read his story below (and be sure to check out his Fougasse recipe and best-selling book as well!). Thank you for sharing, Chef Mike!

At the California Culinary Academy we’ve had a Wood Stone 6-footer for a few years now. Like any chef or baker, you figure out through trial and error how to use any piece of equipment to suit your goals. Typically I’ve taught pizza and other flatbreads but not much more than that.

Recently I had the good fortune of working with several wood-fired ovens in Rome. Some of them historic, like the one at Forni Campo di Fiore, and some of them new models part of a franchise called Pizza Re.

I was struck by how differently each oven was asked to perform and how different textures and flavors resulted from the same four ingredients of flour, water, yeast, and (the “Roman reduction” to 1%) salt. That was when I called Tim Green at Wood Stone to teach me how to finesse my gas-fired hearth oven to create more variety in my breads.

Being a Jersey Boy from the Boardwalk in Ocean City, it was mandatory that Tim teach me the techniques specific to the pies of my young surfing days. The entire process to achieving the crust’s flavor and texture is unique to that Jersey specialty.

But how to re-create those contrasting textures and varied “leopard skin” crust colorations of the Naples Pizza I had recently come to love? To the untrained eye the techniques appear similar–stretching a dough, topping it, and peeling it onto the hearth.

With Tim’s guidance I saw how the shaping gestures and use of “top heat” are only two of the differences between these two pies. In some ways it seemed to parallel that a chef can start with a one-inch sirloin and sear it Pittsburgh-rare or he can transform it into a juicy hambuger for a toasted Brioche Bun. The techniques were strikingly different.

The artisan bread baker in me suddenly took hold. Here was a colleague who’s expertise could extract different results by varying floor temps, positions within the baking chamber, and on and on.

It reminded me a lot of how I teach students to gain a “feel” for their flour. Using sensory analysis techniques, I develop each student’s ability to feel his flour and understand things like its relative humidity, degree of granulation, and protein content.

Seemed Tim’s teaching was leading me in that same direction, to understand the range and number of notes and chords this old world instrument was capable of sounding. Provided you struck the instrument in just the right way.

The quickest way for me to get a grip on this new approach was to bake some of the “daily standards” of the craft bread repertoire: San Francisco SourDough, Rustic French Loaves, and the Fougasse Flatbread from the south of France. If I could make and bake these three different breads in the Wood Stone ovens, I would come to understand a lot more about the richness these ovens can bring to the craft bakers menu.

I’ll focus on the Fougasse because its story is closely linked to wood-fired ovens baking. We’re now in a time long ago when technology like thermostats and thermocouples had not yet appeared, the days when the idea of a “bain marie” was the newest and most popular oven APP.

Raking out their embers and washing the hearth floor, ingenious French bakers in and around the Provence region took pieces of dough, stretch them thinly, and opened their surface areas with a fanciful scoring.

Tossed onto different parts of the oven floor and baked for a set time. Pulled from the oven and examined. These flatbreads would tell the baker what parts of the oven were hotter, cooler, or just right.

The enterprising baker, so the story goes, took to brushing these with olive oil and topping them with local herbs like rosemary and lavender. Called them Fougasse. Which is a linguistic cousin to the Italian Focaccia, both deriving from the Latin root Focus, meaning oven. The focus of the cooking area or kitchen.

Holiday tradition in Provence dictates a table be garnished with 13 Fougasses of various shapes and toppings. Savory and sweet, shaped by all members of the family who share in the celebration.

Searching the web for current versions of this bread you can find any number of exotic and decorative shapes, mostly thin and crisp. The oldest records of the bread indicate its being a thicker (about one inch) bread with a longer shelf life than the extreme cracker-like flatbreads we might see today.

It’s the thicker, more bread-like version that interested me more as a craft baker. I was exploring the oven’s effects on more substantial weights of shapes like the sourdough boule and rustic French miche.

In one of those elusive moments in a professional culinarian’s career, I found myself side by side with an equally skilled colleague. Tim was able to take my understanding and execution of three simple artisan breads and translate for me how they are to bake with better reliability in these Wood Stone ovens, whether gas-or wood-fired.

Everything else seemed to drift away silently. Here was a rare moment when skills are exchanged, language is specific to the techniques at hand. Onlookers would know to watch to silence for the moment was as magical as it was rare.

A technician of any discipline knows the story I tell. When you become one with the tool.

When the oven speaks to you and suddently you understand the new vocabulary it uses to draw you further into its grasp.

Shaking our heads and taking a deep breath or two, Chef Tim and I looked at our products. For an oven-guy like Tim and a bread-guy like myself, the mutual exchange of ideas and knowledge had happened almost silently during our handling of these breads. Both of us had briefly seen the possibilities the other was bringing to the table. Or the oven, in this case.

Now back in San Francisco, I sweep out the dust of my cold hearth oven and begin to visualize how my artisan breads and my students’ will take on changed personalities as I explore the new world this old world piece of equipment brings into the bakeshop.

Here’s my formula and procedure for the Fougasse:

FOUGASSE LEAF BREAD ©

Makes three 1# flatbreads

- Water 510 g 1# 2 oz

- dry yeast 14 g 1/2 oz

- Bread Flour 340 g 12 oz

- Extra Virgin 45 g 1 1/2 oz

- sugar 20 g 2/3 oz

- Bread Flour 450 g 1 #

- salt 15 g 1/2 oz

Procedure:

- Rehydrate yeast. Blend in Flour. Ferment for 45 m @ 84°.

- Add oil and sugar.

- Add Flour and salt.

- Develop dough on low speed for 4 minutes

- Ferment 1h 00 @ 84°, with one turn at 30 m.

- Divide dough into rounds. Rest 20 m;

- Roll dough into triangle, 9″ x 12″. Rest 5 m;

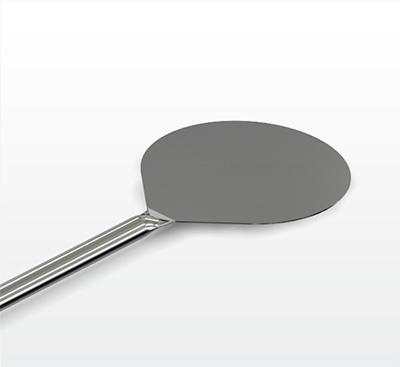

- Score dough with pizza cutter, Stretch dough as desired to open holes.

- Brush with olive oil, sprinkle with coarse salt. Rest 5 m.

- Bake.

Optionally, brush with extra virgin olive oil while cooling bread on a rack.

© Michael Kalanty, How To Bake Bread: The Five Families of Bread, Red Seal Books, 2009

Chef Mike Kalanty is an author and artisan baker. He teaches craft bread baking in culinary schools across the country, in Europe, and in South America. He often works in product development for the commercial baked goods industry.

His first book, “How To Bake Bread”, was named “Best Bread Book in the World” at the Paris Cookbook Fair. Red Seal Books, the publisher, offers the book at a 30% discount to industry professionals on Amazon.com.

Just back from the wood-fired ovens of Rome, ChefMike is fascinated with Pizza Bianca and its applications in American bakery and restaurant menus. He will be presenting his findings about this Etruscan flatbread at the American Culinary Federation’s national convention in Texas later this month.

He can be reached at ChefMike33@aol.com